Whap! The resounding smack of an orca’s pectoral fin against the water signals a playful hello. A deep huff, accompanied by a cloud of steamy vapor rises from the sea as a gray whale surfaces to breathe. An explosive “whoosh” elicits “oohs” and “ahhs” as a mighty humpback bursts from the ocean, twirls and completes a mesmerizing breach.

Hello whales!

There are few places in the world like the Pacific Northwest where one can find gray, minke, humpback as well as two types of orca whales all within reach on a Seattle whale watching trip. Let us introduce you to these remarkable mammals as you explore our Seattle whale watching guide.

Mammal-Eating Orca Whales (Bigg’s or Transient Orcas)

Best Time to View: May-Oct

Book Now: Seattle Whale Watching Tour (Half-Day)

Often seen during the spring in the Salish Sea, mammal-eating orcas hunt other marine animals that feed on the herring in our waters from May to October. The whales’ food source is mainly seals, sea lions, porpoises and occasionally larger whale species.

Roaming up and down the coast between Alaska and California, mammal-eating orcas travel together in small pods. The group is usually made up of one to seven whales, such as a mother and her direct offspring. These mammal-eating orcas have a thriving population, with, an estimated total population of 500, as of 2018.

While the mammal-eating orcas cruise through our waters around the same time of year as the salmon-eating orca whales, they do not share the same vocalizations as them. As such, there is no known socializing, interaction or breeding between the two types of orca whales. In fact, they seem to actively avoid each other.

How to Spot Them

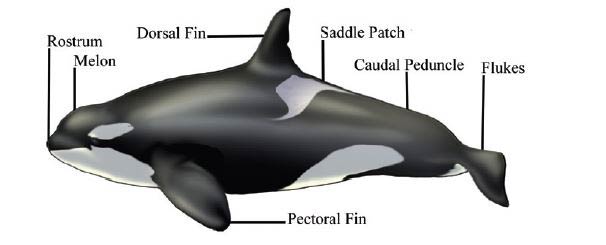

Despite their differences in behavior, it is challenging to distinguish between the two types of orca whales physically. The largest of the dolphin family, both types of male orcas average 27 feet in length and weigh eight tons with dorsal fins growing as high as 6 feet. The females are smaller, growing to an average of 23 feet and weighing six tons. Yet, to the trained eye, it is possible to tell them apart by the subtle differences in their markings.

According to former FRS Clipper naturalist, Justine Buckmaster, “Typically the dorsal fins on mammal-eating whales are very sharp and pointed, very triangular. Whereas on a salmon-eating orca, the fins are more curved in the back.” Buckmaster also noted the differences between the orcas’ saddle patches, the grayish-white marks found behind an orca’s dorsal fin.

She continued, “On a mammal-eating orca, the saddle patch is all one solid color, and the shape is quite a bit wider than those on a resident orca. Likewise, the whale’s white eye patches slope downward slightly, while on a salmon-eating orca they are more horizontal and parallel with the white chin patch on their lower jaw.”

When watching for these magnificent mammals, scan the horizon for black dorsal fins slicing through the water, a telltale sign of an approaching whale.

Salmon-Eating Orca Whales (Southern Resident Orcas)

Most Common Time Spotted in Salish Sea: May-Oct

IMPORTANT: In accordance with state whale watching regulations, FRS Clipper takes all precautions to not engage in any form of whale watching with salmon-eating orcas. Any sightings of salmon-eating orcas are reported to the appropriate partner agencies for the purpose of continued research and tracking of this population of whales.

Unlike mammal-eating orcas, salmon-eating orcas have a smaller and more defined traveling range. They typically spend four to seven months of the year in the Salish Sea. The whales travel in three distinct family groups made up of 20-40 whales, known as the J, K and L pods. Family oriented and social, the orcas interact, socialize and breed with other resident pods, but won’t change from one pod to another.

As of January 1, 2021, there were 74 salmon-eating orcas. There are several reasons why the numbers of our cherished whales may be dwindling. Yet, their diminishing food supply is clearly a leading cause and having a drastic impact on the species’ ability to survive. Salmon-eating orcas rely specifically on the Chinook salmon for more than 70% of their diet. An adult resident orca needs 100-300 pounds of food a day, which is about 40 salmon a day.

Unfortunately, over time, changes in salmon habitat and water conditions are causing substantial decreases in the Chinook salmon runs. As a result, the salmon-eating orca whales have to work longer and harder to find the food they need to survive. In short, they must burn through their reserve fat storages for energy, setting them up for health issues and death.

One of the most impactful ways to help protect the ocean and our salmon-eating orca whales is through responsible wildlife viewing, by following the Pacific Whale Watching Association’s (PWWA) safe viewing guidelines. Whale watching vessels are often the first to spot and report problems involving whales, such as whale injuries or entanglements. The vessel also alerts nearby boaters to slow down and use caution when whales in the area via active radio communications and by flying the whale watching warning flag.

Our team of expert, research-based naturalists also collect data in real time and report it back to whale research organizations such as The Whale Museum to track the health of local whales. While observing safe viewing guidelines and supporting Chinook salmon habitat restoration are two of the most important steps to protect southern resident killer whales, we strongly encourage also visiting the Center for Whale Research’s conservation page to learn more best practices to protect our cherished whales.

How to Spot Them

With their striking white and black markings and towering dorsal fins (they grow as high as six feet on male orcas, and up two feet on female orcas), there is a mystical quality to these iconic species that have occupied our waters for hundreds of years. To catch sight of them, watch the horizon for misty bursts of whale exhalation known as blow. This vapor is a sign a whale is coming to the surface to breathe.

Fascinating and impressive creatures by any measure, orcas display a variety of behaviors that serve different purposes. Ranging from tactical to playful, keep an eye out for these signature moves when searching for orcas in the Salish Sea:

- Spyhopping: When an orca pokes its head above the surface of the water to get a peek at what is happening out of the water.

- Breaching: When an orca leaps out of the water head first and crashes down on its back or side, making a loud splash. This behavior is a form of communication and play between whales.

- Cartwheeling: An upside-down breach! A whale will throw its flukes and lower body out of the water from one side to the other while keeping its head submerged. Like breaching, this likely a form of play.

- Tail Lobbing: When a whale slaps its pectoral fins or tail on the surface of the water repeatedly, which is thought to be a form of communication between whales or a means of stunning prey.

- Porpoising or Speed Surfing: When a whale torpedoes in and out of the water in a rapid series of short, shallow arcs while swimming. This allows the orcas to reach speeds of up to 30 miles per hour.

Humpback Whales

Best Time to View: May-Oct

Book Now: Seattle Whale Watching Tour (Half-Day)

Once an infrequent sight in the Salish Sea, humpback whales are becoming frequent visitors to the Pacific Northwest. This “humpback comeback” is due to a rebounding North Pacific whale population, which now numbers more than 20,000.

The population had dwindled to about 1,600 before whale hunting was banned in 1966. Local naturalists also speculate the recent increase of whales in our region is due to the lack of sustainable food sources in their normal feeding areas further north. Clipper Naturalist, Stephanie Raymond, notes, “We experienced a massive resurgence of humpback activity in the Northwest unlike any other in recent history, with the group feeding in the Salish Sea in 2016 being the largest seen in more than 100 years.”

Migratory by nature, humpbacks spend their summers along the Pacific Northwest coast and return to winter breeding areas in either Hawaii or off the Central American coast. Buckmaster says, “Generally speaking, May-June through early fall is the best time to see humpbacks as they return to the Salish Sea to feed on spawning herring.”

How to Spot Them

Weighing in at 40-tons and reaching up to 50-feet in length, humpbacks are the largest species of whale in the Salish Sea. They have dark gray backs and have a small crescent-shaped dorsal fin perched atop their humped back.

They also have long, pectoral fins that are lighter in color than the rest of their bodies. Individual humpbacks are recognizable by the shape and markings of their tail flukes at the beginning of a deep dive. These acrobatic performers are often popping out of the water for mighty breaches, twisting and whirling through the air. They have also been seen teaming up with other humpbacks to bubble net feed.

Minke Whales

Best Time to View: May-Oct

Book Now: Seattle Whale Watching Tour (Half-Day)

Growing up to 30-feet-long and weighing between five to ten-tons, minke whales are the smallest of the baleen whales. FRS Clipper naturalist Stephanie Raymond explains the minke whales were named after a Norwegian whaler who was known for overestimating the size of the whales he caught. Whalers started calling the smaller whales “minke’s whales” as a joke, and the name stuck.

While minkes may be diminutive, their vocals pack a powerful punch. One of the loudest whales in the ocean, the eerie, low-frequency pulses (think of the sound of a Star Wars lightsaber) and boings produced by minkes can reach up to 152 decibels (as loud as a jet plane taking off).

Primarily solo travelers, but occasionally seen in groups of up to three whales, minke spend most of their time feeding. To eat, the whale takes in a huge gulp of water. Then, using its tongue, pushes the water back out of its mouth catching small fish and plankton in its bristly baleen “strainers.”

The whales favor the PNW’s moderate temperatures in the summer, making May through early fall the best time to find minkes in Washington waters before they migrate to warmer locales during the winter.

How to Spot Them

To spot a minke, watch for their broad, black back and small dorsal fin. If you’re still not sure you are looking at a minke, their white underside, white patches on both front flippers and a pale chevron behind their heads are clear giveaways.

Although minkes are not as acrobatic as orcas, you may be lucky and catch one of their rare water shows. They do breach, usually three times in a row, and make dolphin-esque dives into the water.

Gray Whales

Best Time to View: March-May

Book Now: Seattle Gray Whale Watching Tour

Like clockwork, the arrival of the gray whales in the waters off Washington signals the arrival of spring in the Pacific Northwest. True long-haul travelers, gray whales have one of the farthest migrations of any animals on the planet. These ultra-marathoners travel up to 12,000 miles round trip on their annual journey from the waters off Mexico’s Pacific Coast to the Bering and Chukchi Sea near Alaska.

The best time for gray whale watching is in March through May, when they detour from their off-shore journey to fuel up in our waters. Scientists believe gray whales started visiting the Salish Sea when their food sources became scarce. They kept returning after discovering dense beds of tasty ghost shrimp at the south end of Camano and Whidbey Islands near Seattle.

Buckmaster, states: “The gray whales of Puget Sound are called the ‘Sounders.’ They are the same 10 or so gray whales that return to this area almost yearly. The males return every year, while the females usually visit biennially. When the females have their calves with them on their migration to the Bering Sea, they skip Puget Sound.

Buckmaster explains the mature whales have a risky feeding strategy to get ghost shrimp. She says, “Ghost shrimp are found very close to the shore, so gray whales will get right up to the beach during high tide when the water is at least 10 feet deep — just deep enough to submerge a gray whale. They then turn over onto their side, suck up a large mouthful of mud and silt from the sea floor and filter it out their baleen. This activity would be hazardous for a baby.”

How to Spot Them

One of the easiest ways to spot these massive creatures (they can reach up to 50-feet in length and weigh up to 35 tons – the equivalent of five adult male African elephants!) is to look for a high, heart-shaped misty jet of vapor from the whale’s blow when they surface.

Additionally, keep an eye out for their massive, 10-foot-wide tails when they start a dive. Similar to a fingerprint, the clusters of barnacles speckling their tails, head and bodies vary in shape, size and color and are unique to each animal.

What to Bring on a Whale Watching Tour in Seattle

When seeking out the magnificent creatures that call the Pacific Ocean home, it is important to bring along the proper gear. Weather in the Pacific Northwest varies greatly by season. Temperatures are usually cooler on the water, even during peak summer months and particularly during morning hours. Be sure to dress warm with extra layers handy to adjust to changing temperatures.

Not sure what else to bring? Check out our recommended picks and packing guide to take your whale watching adventure to the next level.

- Hat

- Sunglasses

- Sunscreen

- Binoculars (Don’t worry if you don’t have a pair or forget to pack them along, we have pairs for rent onboard.)

- Camera/video camera

- Extra batteries

- Water bottle (no glass please)

- Snacks and/or lunch or dinner (We also carry food for purchase onboard.)

- Wear flat shoes preferably with a rubber bottom, such as tennis shoes

- Rain jacket or windbreaker

- Gloves (optional)

- Motion sickness medication (If you’re prone to motion sickness (or even if you’re not), pack some form of medication just in case. Ginger is also an effective natural treatment. Forgot to bring them along? Our crew can provide you with non-prescription seasick remedies onboard.)

With spring bringing the Emerald City back to life, there are more opportunities than ever to embrace our sunnier weather and hop on an epic whale watching trip to catch sight of these amazing marine mammals. Whether it is your first time on the water or one of many, there is nothing more magical than seeing whales jump, splash and play in our local waters. You can rest assured you’ll get a whale of a view!

Photo Blocks: Naturalist Justine Buckmaster